Written by Shannon Marshall • Header Image by Lisa Scott

Birds hold a special place in the rich tapestry of British Columbia’s biodiversity. They’re more than just animals; they’re our neighbours, our constant companions. Spend enough time in any woods nearby or on a leisurely stroll down your street, and you’ll find plenty of avian locals. Personally, I recently delved into birdwatching while learning to discern the calls of the birds that inhabit the woods behind my house and my local beach. It’s a shift; I used to always walk with music in my ears, a temporary escape from the world. Lately, I’ve embraced a new habit – walking without earbuds, listening to the symphony of my bird neighbours. Now, I can anticipate which species I’ll encounter in different corners of the woods or beach.

With the shifting seasons, British Columbia’s landscape transforms into a dynamic hub of avian activity. Summer’s calm shifts into the brisk hustle of fall, with birds coming in from all corners to enjoy the province’s many ecosystems. B.C. morphs into a sanctuary, offering refuge to birds on their extraordinary journeys. While some will remain companions on my chilly walks through the damp woods and misty beaches, many birds will also bid temporary farewells. Birds remind us of nature’s ever-changing rhythm.

Trumpeter swans at Somenos Marsh, photographed by Karen Barry

But just how do birds make these incredible journeys? Understanding their adventures, has led me to an even deeper appreciation. Now, let’s dive into the extraordinary lives of migrating birds.

British Columbia lies in the path of the Pacific Flyway, a major migratory route extending from Alaska to Patagonia, spanning an astounding 15,000 kilometers. During fall migration, the numbers of birds swell nearly threefold as adults, along with their young, head south in search of more hospitable temperatures.

One of the most iconic migrating species is the sooty shearwater. Having feasted in the plentiful waters of the North Pacific, in the fall, they embark on a journey back to their breeding grounds all the way in New Zealand. This epic migration is more than 64,000 km round trip!

In mid-September, Vancouver Island becomes a bustling stopover for many migratory raptor species as they are attracted by the annual salmon run. The skies become full of turkey vultures, hawks, falcons, kestrels, harriers, and ospreys as they converge in East Sooke Park before crossing the Juan de Fuca Strait. It is also common to see hundreds of bald eagles in December feasting off salmon from the Squamish River dyke trail, so bring your binoculars!

In October and November, Delta’s George C. Reifel Migratory Bird Sanctuary, south of Vancouver, also becomes a hub for up to 80,000 lesser snow geese. These travellers embark on a 5000-km journey from Russia’s Wrangel Island, making crucial stopovers at the Fraser and Skagit estuaries before reaching their destination. Their journey is a testament to their resilience and adaptability as they navigate diverse landscapes and overcome obstacles to find suitable wintering grounds.

Left: A bald eagle photographed by Sammy Penner. Right: Snow geese photographed by Charlotte Sherry.

Now that we’ve covered some of the bird species that take part in epic migrations, let’s delve into some fascinating facts about their journeys.

Birds use a combination of remarkable techniques for navigation. This includes celestial navigation, where they use the sun, moon, and stars as navigational cues. They may also have tiny grains of magnetite in their beaks, acting as natural compasses, allowing them to detect the Earth’s magnetic field.

Before embarking on their long journeys, migratory birds will often engage in a period of increased feeding called hyperphagia. During this time, they accumulate fat reserves, which serve as their primary source of energy during long flights.

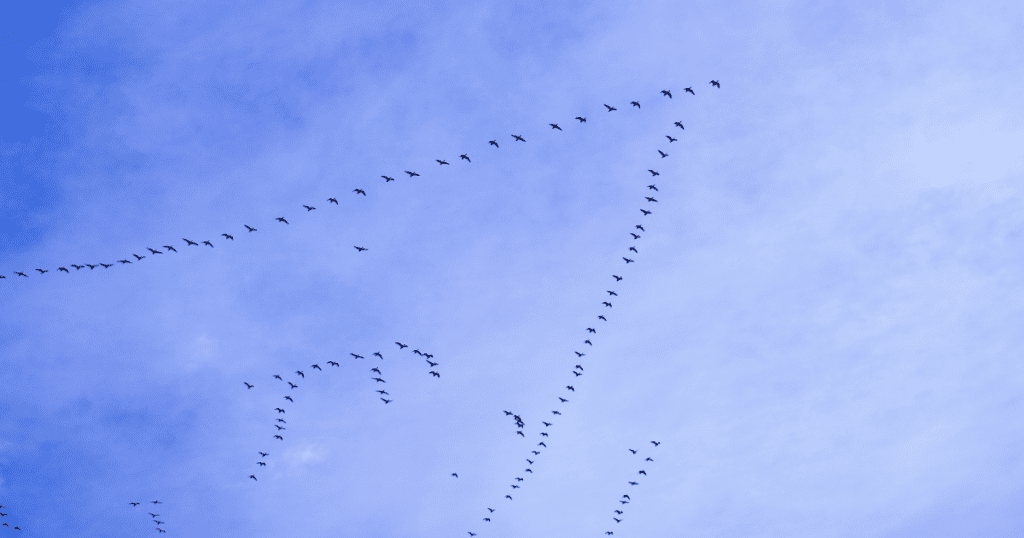

Many migratory birds have also evolved efficient flight mechanics. Some will travel at high altitudes, where the thinner air requires less energy for wing beats. Some species also travel in flocks which helps save energy. Flying together reduces wind resistance and improves their navigation. V-formations are a classic example of this collaborative approach which are common to see in B.C.’s skies.

Snow geese migrating overhead at Boundary Bay.

The migration routes of birds can often vary. Some will follow coastlines, while others cut directly across continents. The route they choose often depends on facts like weather conditions and available food sources. Wetlands, coastlines, and mature forests serve as critical stopover points for migratory birds. These habitats provide essential rest, food, and shelter during their long and exhausting journeys.

The loss and degradation of these habitats, a consequence of rapid urban development and expansive agriculture, loom as significant threats. Climate change further compounds these challenges, altering weather patterns and affecting food and nesting availability. Because of this, many of B.C.’s migratory birds are threatened such as the western grebe and marbled murrelet. Other species, such as the sandhill crane, are no longer considered threatened, but still remain intrinsically vulnerable to threats due to their selected breeding, staging, and wintering sites.

The Nature Trust of British Columbia recognizes the pivotal role of these habitats in sustaining migratory birds and their journeys. By protecting and restoring land, The Nature Trust ensures vital stopover points, feeding areas, and breeding grounds remain accessible.

As we stand witness to these journeys every year and the magnificence of migratory birds, let us remember that their survival hinges on the preservation of their habitats. Supporting organizations like the Nature Trust of British Columbia in their conservation efforts ensures that our familiar neighbours come back year after year.

And, thanks to international partnerships like the North American Wetlands Conservation Act (NAWCA), your US dollar donation to conserve bird habitat will go even further. Learn more about the NAWCA program here.

Least sandpiper at the Englishman River.

Editor’s note: In a previous version, this article erroneously described sandhill cranes as threated. The article was edited on November 28, 2023 to correct this error.

Written by Shannon Marshall

Written by Shannon Marshall