Curtis Rispin, the Nature Trust of BC’s Senior Restoration Technician on Vancouver Island, headed to the Fulmore River estuary and the Shoal Creek estuary for some field work. We were lucky enough to get the inside scoop on his trip along with some stunning photos!

Field Work at Shoal Creek and the Fulmore River Estuary – Sept 9, 2021

By: Curtis Rispin

My phone alarm goes off in the living room, forcing me to get up and out of bed at 4:30 am, before it wakes my 2 year-old son. While waiting for the water to boil for my coffee, I double check my gear, ensuring I haven’t forgotten anything important. Bear spray, binoculars, computer, air horn, rain jacket, chargers, etc. – everything is there, and the rest of the field equipment has been stowed away in the car the previous night. Out the door by 4:50 am and I am on my way to pick up my coworker, Sonja, and then we are northward bound.

Our goal for this trip is to collect sediment cores at four locations in the estuary complex. This area is comprised of two estuaries separated by a headland – the Fulmore River estuary and the Shoal Creek estuary in the traditional territory of the Tlowitsis First Nation. Sediment cores are collected for later analysis at the Estuarine Ecology Lab at Western Washington University to estimate long-term sediment build-up in the salt marsh. Additionally, we have two rSET’s (rod surface elevation tables) that are used to measure annual changes in sediments. Both of these datasets, along with other metrics derived from the Marsh Resilience to Sea-level Rise (MARS) tool, contribute to our understanding of the resilience estuaries might have to a changing climate.

We arrive at Kelsey Bay and meet our boat captain, Andy, from the Tlowitsis Guardian Watchmen, as well as Matt from the University of British Columbia and his assistant Richard. Matt and Richard are tagging along for a separate project, collecting sediment samples from seagrass beds for Matt’s Masters’ research on the carbon storage potential of these ecosystems.

On board the Tlowitsis First Nation Guardian Watchmen boat.

We load the boat full of our gear and depart north east, up Johnstone Strait towards Port Neville. The water is calm, a lucky break in a strait that can blow up quickly. Within a few minutes of leaving the marina, we spot a Humpback whale on the starboard side of the boat, heading in the same direction. A few minutes later, we spot the first of hundreds of Pacific white-sided dolphins popping up on all sides of the boat. Andy mentions that he’s observed very few whales in the strait this summer, a stretch of water that he’s spent countless hours on. Combined with the early morning and the excitement of whales and dolphins, I forget to keep my eye out for the Short-tailed and Sooty shearwater birds. They have have been making an unprecedented appearance all over eastern Vancouver Island and the Salish Sea, travelling from the tip of the island south in large numbers. To my knowledge, the reason for this rare event isn’t fully understood yet, but hopefully it’s not a forewarning of a lack of food or environmental stressors out in open waters.

Passing by Port Neville and entering the calm waters of the inlet, we join hundreds of seabirds, including Red-necked Grebes, Common and Pacific Loons, Pelagic and Double-crested Cormorants, Bonaparte’s Gulls, Glaucous-winged Gulls, Short-billed Gulls (formerly Mew), Common Mergansers and many others. We follow the inlet towards the estuary, but before we can get into the inlet, we first need to stop and pick up a small skiff, as the mudflats associated with this site don’t allow the larger Guardian boat we travelled on to get anywhere near the estuary.

Andy prepares the skiff for the crew to access the estuary.

Once the skiff has been loaded up with our gear, we leave the comfort of the bigger boat behind and Sonja steers us into the Fulmore estuary. The tide is low, forcing us to find and follow the river channel that snakes its way into the estuary. Matt and Richard find a large bed of eelgrass, and so we drop them off in the soft mud at the far reaches of the estuary where they can collect their samples.

Matt and Richard navigating the soft mud of the outer estuary.

Sonja and I continue navigating up the channel towards our targeted sites. As we come around a bend in the channel, remnants of a fish weir (a structure used to trap fish), once used by the Tlowitsis First Nation poke through the sediment, extending from the top of the bank and into the channel below. Thousands of these stakes can be seen all over the estuary and up into the river, where Coho, Pink, Chinook and Sockeye salmon have historically returned to spawn in the river and in Fulmore Lake.

While following the river channel into the estuary, we notice stakes from a fish weir along the bank.

Getting closer to the salt marsh, I scan the area with my binoculars to ensure there are no Grizzly bears awaiting our arrival. Luckily, the only thing I see is a Spotted Sandpiper, teetering and bobbing as it follows the rocky shoreline. Getting further up the channel, the water starts to disappear under the boat, so Sonja and I have to hop out and push it the rest of the way. Once we arrive at the salt marsh, we collect our sediment cores at two locations in the estuary using PVC pipes hammered into the ground until we get about 70 cm of sediment. We dig out the core and seal it up as it will be traveling with us for the remainder of the day. We hop back into the boat and follow the channel out towards to bay, finding Matt and Richard awaiting their pick-up after successfully collecting their own samples.

Matt and Richard awaiting their pick up before heading towards the Shoal estuary.

With the Fulmore now complete, we switch our focus to the Shoal, an estuary that has proven incredibly difficult to access over the last two years. Between bears and tides, we have attempted on more than one occasion to complete work there and came out empty handed. The extensive tidal mudflats, the meandering creek channel that holds no more than a couple of inches of water at low tide, and the handful of large Grizzlies that hang out in the marsh mean it can take hours to reach our intended site. However, careful planning on this trip can pay off, and as we start our way up the channel, the tide starts to rise. We run out of water on a number of occasions while pulling and pushing the boat upstream, but within a few minutes each time, the tide comes up, and the boat begins to float again. Passing the time while waiting for the water levels to rise, I scan the mudflats and spot a small flock of about fifteen Western Sandpipers probing the soft sediment, filling up with food during their southward migration. We also spot Canada Geese and a few flocks of dabbling ducks – including Mallards, Northern Pintails, and Green-winged Teals.

The Shoal estuary proving difficult to get to once again.

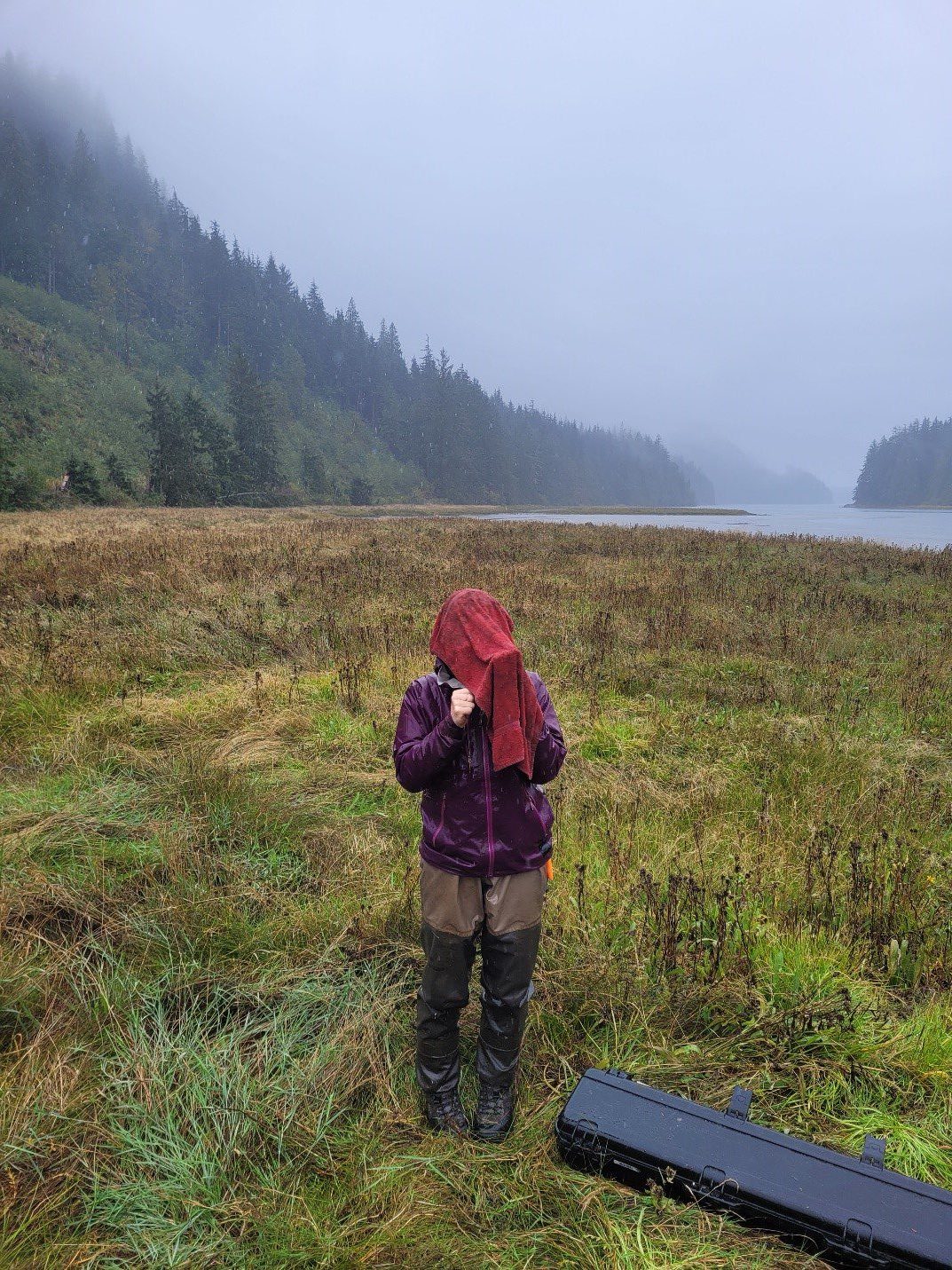

After about an hour of making our way up the small channel, we reach our first site and collect one sediment core and take our rSET measurements. The rain, now heavy for the first time all day, makes recording our notes difficult on our touchscreen devices, leaving Sonja to find shelter under a mud covered towel.

Sonja finding cover from the rain.

With our third site complete, I pull up my foggy binoculars and scan again towards our fourth and final location a few hundred meters up stream. This time, three more Spotted Sandpipers hop along the shore, then take flight up the channel. Following the birds, my eyes catch sight of a large brown object against the yellowing vegetation. It doesn’t move, and the fog in my binoculars make it difficult to focus, but then the shape of two ears appear, and slight movements confirm my initial thoughts. This large Grizzly is precisely where we need to be. After a few minutes of watching the bear, we decide to boat up the channel, hoping that the presence of four humans and the sound of a boat motor would nudge the bear into the nearby forest. Seemingly unbothered, the bear hardly even looks in our direction as we park the boat in a small channel on the opposite bank across from the bear. Another few minutes pass by while we weigh our options of getting to our site, but by now, the bear has its nose pointed towards the sky, as it gets a scent of the estuary intruders. Standing up, it gets a better look at us and decides that it will move along.

A local Grizzly bear in the Shoal estuary.

Disappearing and reappearing as it crosses through tidal channels, the bear is in no hurry, and it walks through the estuary at a slow, meandering pace until it reaches the forest edge. With the bear out of sight, we swiftly capitalize on the opportunity and jump back in the boat and cross the channel to get to our final location.

Sonja collecting measurements from an rSET platform.

Working quickly, Sonja and I hammer in the sediment core pipe, while Matt keeps watch for the bear just in case it reemerges. Richard then takes over, digging the core out of the ground, while Sonja and I proceed to collect our rSET measurements. Once we have completed all of our objectives, we jump back in the skiff, the rain still pouring down, and Sonja steers us back to the larger Guardian boat, where Andy is patiently waiting for us to return. We unload the skiff and board the boat for a cold, wet ride back to Kelsey Bay.

The Nature Trust of BC is trying to acquire 320 acres of land in the Shoal Creek Estuary. This property consists of two parcels that will be acquired over two years. In line with the Pacific Flyway, this area is part of the migration route extending along the Pacific from Alaska to the southern tip of South America. With millions of birds stopping over in these wetlands and estuaries each year, it is integral that we work to protect this property as best we can. We currently need $350,000 in order to purchase this property and protect it now and into the future. To donate click here.