British Columbia’s diverse landscapes and plentiful waters are a sanctuary for rich biodiversity. Among its many natural treasures, BC boasts numerous endemic species. Endemism refers to the ecological phenomenon where a species is native, restricted to a specific geographic area, and not found anywhere else in the world. These unique species have evolved and adapted to the specific environmental conditions, ecological niches, and geographical boundaries of their range.

Endemic species play a crucial role in maintaining the delicate balance of the province’s ecosystems, showcasing the importance of preserving and protecting their habitats. This article will introduce you to five remarkable creatures and explore why they are vital to British Columbia’s ecological well-being.

Vancouver Island Black Bear (Ursis americanus vancouveri)

Discover the Vancouver Island black bear, a unique subspecies of the mainland black bear found only within the forests of Vancouver Island and its adjacent islands. As compared to their mainland counterparts, this subspecies is distinguished by their consistently darker colouring and larger skulls. These bears have a fascinating origin; evidence suggests their arrival on the island shortly after the last glaciation around 10,000 years ago, as indicated by ancient skeletons found in caves.

Embodying BC’s natural heritage, this endemic species holds deep cultural significance for several Indigenous communities, symbolizing strength, wisdom, and protection. As expert seed dispersers, they also play a pivotal role in shaping the island’s diverse plant communities, supporting the growth of vital flora. Their affinity for salmon during the spawning season also benefits their ecosystems, as leftover carcasses provide a nutrient-rich food source for other wildlife and help fertilize soils.

Embodying BC’s natural heritage, this endemic species holds deep cultural significance for several Indigenous communities, symbolizing strength, wisdom, and protection. As expert seed dispersers, they also play a pivotal role in shaping the island’s diverse plant communities, supporting the growth of vital flora. Their affinity for salmon during the spawning season also benefits their ecosystems, as leftover carcasses provide a nutrient-rich food source for other wildlife and help fertilize soils.

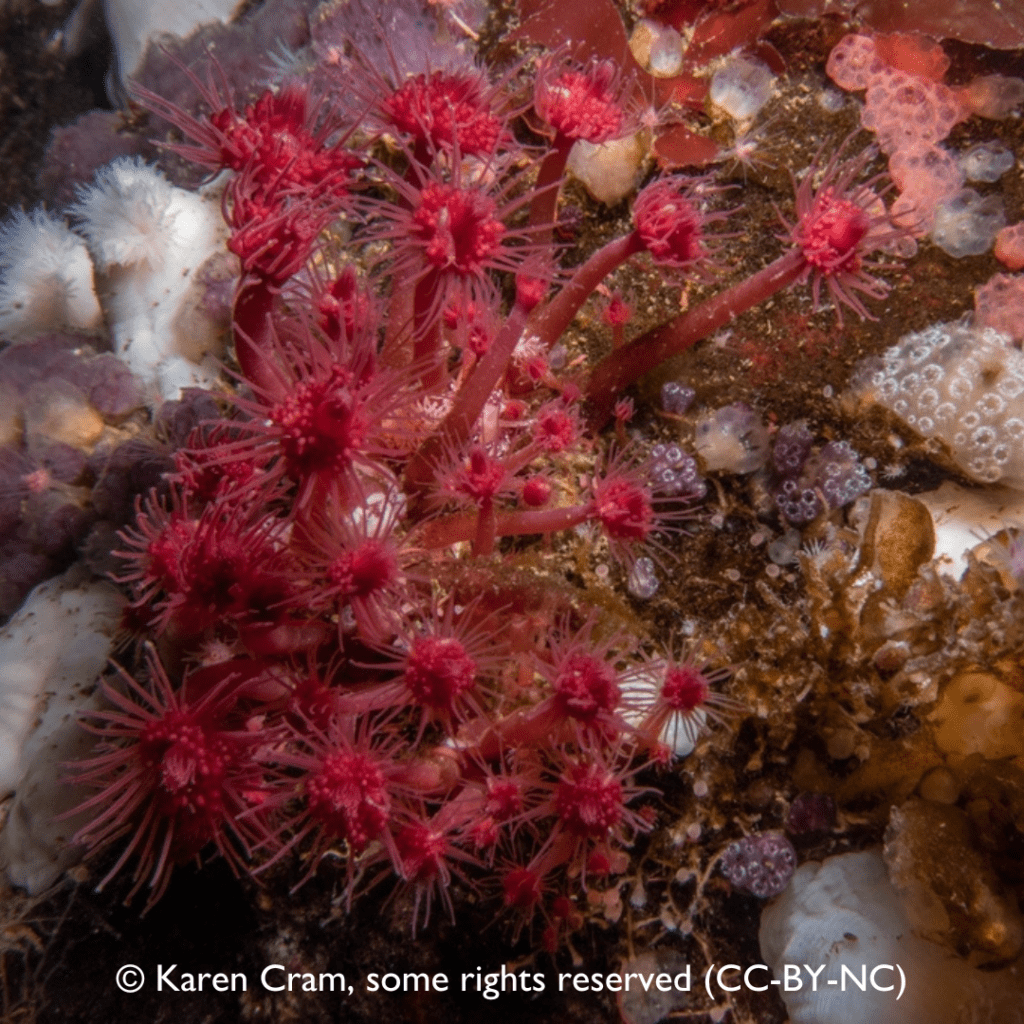

Raspberry Hydroid (Zyzzyzus rubusidaeus)

Meet the extraordinary raspberry hydroid, a marine species found uniquely in BC’s coastal waters near the northern tip of Vancouver Island. True to its name, these hydroids resemble clusters of raspberries adorned with vivid colours, from deep reds to purples and pinks. Interestingly, they were only described as a distinct species in 2013, thanks to the research efforts of Anita Brinkmann-Voss, a scientist from northern Vancouver Island.

This species of hydroid belongs to the phylum Cnidaria, which includes jellyfish, corals, and sea anemones. These marine creature s have a long evolutionary history, with some fossil evidence dating back over 500 million years. Equipped with specialized tentacles containing nematocysts, the raspberry hydroid exhibits a remarkable adaptation in capturing tiny planktonic organisms that drift in the water. Upon contact, the stinging cells immobilize and consume their prey.

s have a long evolutionary history, with some fossil evidence dating back over 500 million years. Equipped with specialized tentacles containing nematocysts, the raspberry hydroid exhibits a remarkable adaptation in capturing tiny planktonic organisms that drift in the water. Upon contact, the stinging cells immobilize and consume their prey.

In BC’s marine ecosystem, the raspberry hydroid plays a vital ecological role, providing essential shelter and habitat for diverse marine organisms. Its intricate structures transform its surroundings into a bustling microenvironment, acting as a nursery for juvenile fish and invertebrates.

Haida Gwaii Varied Thrush (Ixoreus naevius carlottae)

The Haida Gwaii Varied Thrush is a subspecies found nowhere else but on the islands of Haida Gwaii in BC. Its isolated habitat has fostered unique characteristics, setting it apart from other Varied Thrush Populations.

In the dense forests where these birds breed, their sweet, echoing, simple song will be the first clue that they are nearby. Watch for them foraging on the forest floor in small clearings, meanwhile, singing birds will often perch higher in the understory and lower layers of the forest. Catching a glimpse of these elusive birds reveals a stunning combination of slaty gray back and breast band contrasting with a fiery burnt-orange breast and belly. The males are renowned for these vibrant colours, while the females exhibit more subtle hues. Notably, the female Haida Gwaii varied thrush is distinguished by its red tones, as opposed to the mainland thrush’s olive-coloured plumage.

In the dense forests where these birds breed, their sweet, echoing, simple song will be the first clue that they are nearby. Watch for them foraging on the forest floor in small clearings, meanwhile, singing birds will often perch higher in the understory and lower layers of the forest. Catching a glimpse of these elusive birds reveals a stunning combination of slaty gray back and breast band contrasting with a fiery burnt-orange breast and belly. The males are renowned for these vibrant colours, while the females exhibit more subtle hues. Notably, the female Haida Gwaii varied thrush is distinguished by its red tones, as opposed to the mainland thrush’s olive-coloured plumage.

Like other varied thrushes, this subspecies has a wild side, often displaying aggressive behaviours towards each other and other bird species. Males have been known to fiercely defend small feeding territories, asserting their dominance over sparrows, blackbirds, cowbirds, towhees, and juncos. As adaptable foragers, these thrushes feed on insects during the bountiful summer months and switch to a diet of berries and seeds in winter.

Macoun’s Meadowfoam (Limnanthes macouni)

Macoun’s meadowfoam, a small herbaceous plant endemic to Southern Vancouver Island and several adjacent islands, is a true botanical treasure. Initially discovered near Victoria in 1875, this species was believed to be extinct for many years until its rediscovery on Trial Island in 1957. From late March to early May, its white petals and vibrant yellow centers grace the landscape.

This species thrives in open areas and light forests, often found near the Pacific Ocean’s shores. The key to its survival lies in specific ecological conditions, as it prefers wet or submerged habitats in winter and entirely dry habitats during summer. This plant has evolved specialized adaptations to thrive in this habitat, including leaves that are coated with a waxy later, providing protection and reducing water loss in the salty air.

the Pacific Ocean’s shores. The key to its survival lies in specific ecological conditions, as it prefers wet or submerged habitats in winter and entirely dry habitats during summer. This plant has evolved specialized adaptations to thrive in this habitat, including leaves that are coated with a waxy later, providing protection and reducing water loss in the salty air.

The Garry Oak ecosystems that Macoun’s Meadowfoam relies on would not exist without historical cultural management from Indigenous communities, who have been stewarding the land for time immemorial. These traditional ecological practices include low-severity controlled fires, and other maintenance and cultivation techniques. However, ongoing settler-colonialism has put Macoun’s meadowfoam at risk. The natural vegetation of the Garry oak savanna, once abundant in the southern part of Vancouver Island, has significantly diminished due to development pressures. As a result, native plants like Macoun’s meadowfoam, which rely on this ecosystem, face extinction. This is mostly due to habitat destruction and invasive species.

Vancouver Island White-tailed Ptarmigan (Lagopus leucura saxatilis)

The subspecies of white-tailed ptarmigan, endemic to Vancouver Island, showcases a remarkable adaptation to its environment. Like other North American ptarmigan, they possess cryptic plumage that expertly camouflages them against snowy landscapes in winter, where they are entirely white, and rocky terrain in summer, where they exhibit a mottled brown, grey, and white colouration. As the smallest grouse in North America, the Vancouver Island subspecies of white-tailed ptarmigan has unique characteristics. They have shorter wings, heavier bodies, and a more hooked bill compared to their mainland counterparts.

Thriving in various alpine, subalpine, and upper montane habitats year-round, these ptarmigan have diverse dietary preferences. Their omnivorous diet includes buds, stems, seeds, leaves, fruits, and insects. These foraging habits play a crucial role in seed dispersal, promoting the growth and propagation of alpine plant species and ultimately helping the entire ecosystem to thrive.

Thriving in various alpine, subalpine, and upper montane habitats year-round, these ptarmigan have diverse dietary preferences. Their omnivorous diet includes buds, stems, seeds, leaves, fruits, and insects. These foraging habits play a crucial role in seed dispersal, promoting the growth and propagation of alpine plant species and ultimately helping the entire ecosystem to thrive.

Despite their adaptability, this subspecies faces challenges. They are vulnerable to extinction because they live in low densities within patchy habitats characterized by ever-changing environmental conditions. Ski resort developments and forest harvesting are just a few of the human activities altering their environment.

Protect BC’s Biodiversity

Endemic species in British Columbia serve as captivating representatives of the province’s unique biodiversity, underscoring the significance of preserving native ecosystems. While many BC species may exist throughout North America or even globally, some are exclusive to BC, making it their sole refuge. If their habitat is lost, these species face extinction, disappearing entirely from the planet. As responsible stewards of this precious natural heritage, it falls upon us to protect and conserve these endemic species, ensuring that they continue to thrive and enchant future generations.

In honour of BC Day, donate today to safeguard BC’s natural treasures.

Written by Shannon Marshall

Written by Shannon Marshall